Finding criminal ancestors

Many families have skeletons in their genealogical cupboard and finding a criminal ancestor can add drama to your family history.

Some of the most ‘respectable’ families may have turned to petty crime in order to survive and you are likely to find brawlers, trespassers, thieves and poachers. You may even come across a nefarious individual who committed a more serious crime.

There are many records where you might find the shady characters lurking in your family tree and this guide will help you to search them out and to uncover the colourful details of their misdemeanours.

Starting point

Families sometimes pass down myths about legendary family crimes, which can be a good starting point for your investigation. It is well worth interviewing relatives who have such a story to tell and noting down all the details ready for checking them out through your research. Be aware though that stories are often ‘embroidered’ through the generations.

A more general starting point would be to enter the names of your main family lines into the online database searches to see if any basic information comes to light. Begin your search by checking the criminal records available at Ancestry or Findmypast. Both have a comprehensive collection of records and if an individual is flagged as a potential ‘criminal’ then you can follow the clues from there.

The criminal database (1787-1892) at www.ancestry.co.uk includes criminal registers, prison hulk registers and Australian transportation. www.findmypast.co.uk has a number of Special Collections, which comprise records from courts, prisons, industrial schools and workhouses.

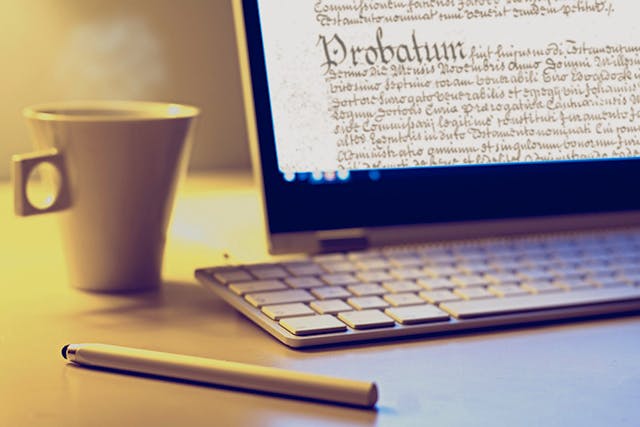

Court records

A basic understanding of the criminal justice system is essential for tracking your ancestor through the courts. During your research, you are most likely to encounter the following types of courts:

1. Petty Sessions – minor offences were usually tried at the petty sessions. These were summary courts with two presiding magistrates and often without a jury. They mostly dealt with petty crimes, such as drunkenness and swearing, rather than more serious cases.

The magistrates were upstanding members of the local community appointed by the Crown to try minor offences. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, police courts took over their work.

2. Quarter sessions – crimes like theft and wilful damage were brought before the county quarter sessions, which comprised a jury and local justices of the peace. They were held four times a year, at Epiphany, Easter, Trinity (mid summer) and Michaelmas.

The High Sheriff presided over the court and a permanent official, the Keeper of the Rolls, was appointed to keep the records. In 1971 the quarter sessions were replaced by the newly formed crown courts.

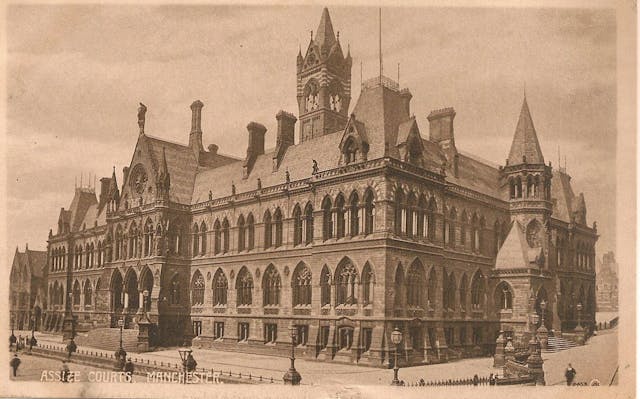

3. Assizes – for the most serious offences, such as homicide, suspects would be tried before the assizes courts, which were presided over by two or more judges who travelled a circuit to hear cases that were deemed too serious or complex for the local justices of the peace. In existence since the 13th century, the assizes were replaced by crown courts in 1971.

The assizes for London, Middlesex and part of the Home Counties were held at the Central Criminal Court of the Old Bailey. Transcripts of the trials held there from 1674 to 1913 are available free to download from www.oldbaileyonline.org

County Record Offices hold original copies of court records from petty sessions and quarter sessions. They may also contain additional supporting documents, such as recognizance books (bonds to ensure the behaviour of an individual) and depositions (statements made under oath). Many record offices have online indexes and copies of individual records can be ordered through their websites.

Records of the assize courts are available at The National Archives in the ASSI series, except for original records of the Old Bailey, which are held at London Metropolitan Archives.

Criminal registers

Criminal registers were created under the auspices of the Home Office as prisoners moved through the penal system. The National Archives at Kew holds lists of all individuals held in prison, whether they were awaiting trial or had been convicted. They give the name of the prisoner, the date and the place of trial, which makes locating your ancestor easier. Series HO 26 covers London and Middlesex (1791-1849) after which date the entries are incorporated into the records for the rest of the country, which are held in series HO 27 (1805-1892). All these records are available online via www.ancestry.co.uk.

The after-trial calendars (1855-1949) are in series CRIM 9 at The National Archives and the Home Office calendars of prisoners (1868-1929) can be found in HO 140. They list all convicts, and the prison records (c1770-1951) can be located in series PCOM 2. www.findmypast.co.uk offers access to these records up to 1934.

Many of the special collections in www.findmypast.co.uk drawn from local record offices holdings include the registers for specific prisons within their area. These can be very comprehensive documents with considerable detail about the nature of the offence, previous convictions and personal information, such as address, spouse and number of children. They even give a full physical description of the prisoner, including height, hair and eye colour, and distinguishing marks, such as scars and pockmarks.

Transportation

From the early 1600s transportation was used as a means of punishment, with the shipping of convicts from the British Isles originally to the West Indies and America.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, British prisons became so overcrowded that transportation was re-introduced, with the first convicts travelling to Australia in 1787 on the First Fleet of Convicts. Individuals awaiting transportation were housed in the notorious prison hulks, which were decommissioned wooden ships initially moored in the river Thames. Transportation to the colonies was ended in 1868.

The National Archives holds the transportation records: HO 8 and HO 9 for the prison hulks, HO 10 for settlers and convicts sent to New South Wales and Tasmania, and HO 11 for the Convict Transportation Registers. www.ancestry.co.uk offers access to the databases for the Hulks (1802-1849) and the First, Second and Third Fleet Australian transportation records. www.findmypast.co.uk also holds hulk records from 1818 to 1832.

There are many websites devoted to transportation, such as Convicts to Australia at http://members.iinet.net.au/~perthdps/convicts/. A simple Google search will enable you to find the most up-to-date ones.

Contemporary newspapers

Local newspapers often published detailed accounts of criminal acts and court cases, sometimes even including verbatim excerpts from the criminal proceedings. Even the most minor crimes were often reported and you may be able to find the colourful detail that is often missing from the rather dry official trial documents.

The British Newspaper Archive website has an excellent collection of digital newspapers, available for a subscription at www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk The online collection currently comprises over 8 million pages and more are being added daily. www.findmypast.co.uk also provides access to the British Library’s online newspapers, offering a wide range of national and local publications.

If you have a UK library card, you will be able to gain free access to The Times Digital Archive, through your library’s website.

The Society of Genealogists

The unique collection of records in the Society of Genealogists’ library holds considerable information about crime in books, records and pamphlets. The SoG’s regional resources contain records that relate directly to criminal ancestors, such as calendars of prisoners, microfiche copies of summary convictions and other court records. There are often copies of family history society publications, which can provide invaluable information and are a useful preparation before making a trip to the County Record Office.

Many of the records at the SoG pre-date the 19th century records widely available elsewhere. In addition, there are some very specific databases such as the Bernau Index, which comprises microfilm copies of 4.5 million surname-indexed slips relating to un-catalogued records from Chancery and Exchequer Court proceedings.

Other publications include general material relating to crime, from smugglers’ memoirs and prison conditions to serial killers and highwaymen. If you can’t locate your ancestor’s name in the online catalogue, enter some key words and you may find entries relating to your specific area of interest. It is well worth coming into the library, if you can, to browse the shelves as they hold many invaluable publications that are not yet available anywhere online.

Conclusion

Finding a criminal ancestor is always an exciting moment in family history research and, apart from learning about an individual’s misdemeanours, crime also gives an insight into how our family lived and often the hardships they had to endure. Once you have found a ‘skeleton’ in your family history cupboard, be sure to write the story for a blog, family book or even a family history magazine.

Further reading

Quarter Sessions Records for Family Historians – Jeremy Gibson (The Family History Partnership, 2007) – available from the SoG online shop

Tracing Your Criminal Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians – Stephen Wade (Pen and Sword, 2009)

Angela Buckley,

June 2014

Join us

As a member, you can make the most of our resources, access our experts, and find a welcoming community of people interested in family history and genealogy.

We all have roots. Let’s find them together.