How to use Census records

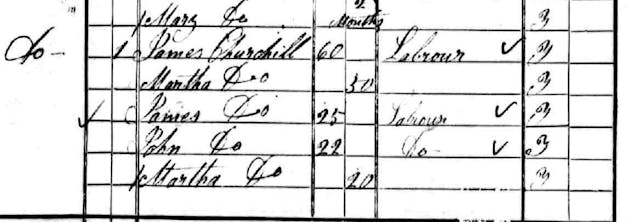

Nineteenth and early twentieth century census returns are key documents in identifying and learning more about our ancestors.

The census returns provide a snapshot of a family living together in a household on the night of the census.

They not only provide evidence which can help to prove lines of descent but they can also place individuals into the more meaningful context of their families and neighbours and the wider framework of their local and social surroundings.

Background

The national censuses were conducted primarily because of the government’s need for information about population growth and distribution in view of the economic and social changes in the UK and Europe in the late 18th century.

They were not intended to provide material for future family historians. So we are very lucky to have such a wealth of detail relating to the greater part of the 19th century and into the early 20th century.

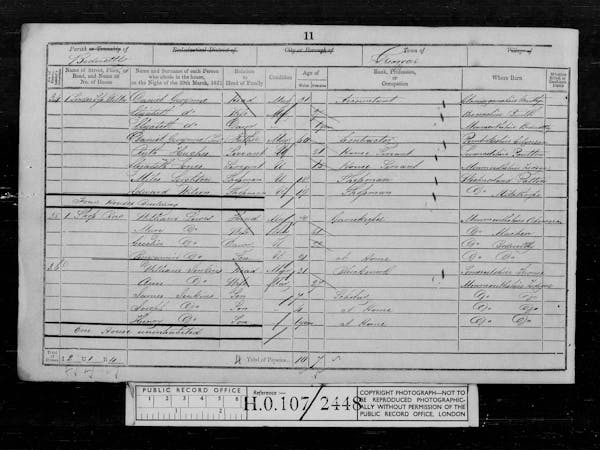

Although some statistical data was provided in censuses taken in the early part of the 19th century, the collection of important information about people first began with the census taken in 1841. It has continued every ten years since, generally with greater detail being provided each time, apart from the war year of 1941. In the past, the returns have been closed to the public for 100 years.

However, the 1911 was made available for research in 2009 although some limited information from this census, such as that recording infirmities or conditions, was withheld until 2012. The 1921 census returns are now available to the public.

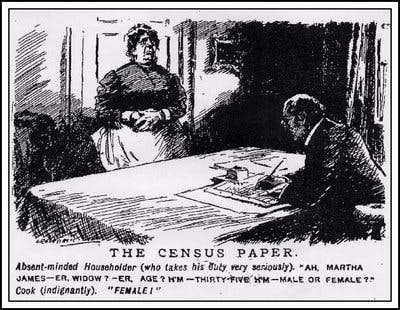

The census documents, up to 1901, which we see are usually not the original forms. Schedules were taken round to each household in advance and details of all the people in the house on census night were filled in by the householder. The forms were then collected by the census enumerator, who might also have to assist in recording details if the householder had difficulty in doing so. The information was copied into an enumeration book by the district registrar.

These were sent, together with the original schedules, via the superintendent district registrar, to the General Register Office in London. It is microfilmed copies of these books which we now have access to. The original books are kept at the National Archives at Kew and are not generally available to the public.

The schedules were usually destroyed after clerks had checked them against the enumeration books, extracted statistical information and made certain notes and ‘corrections’.

The census documents, up to 1901, which we see are usually not the original forms. Schedules were taken round to each household in advance and details of all the people in the house on census night were filled in by the householder.

The forms were then collected by the census enumerator, who might also have to assist in recording details if the householder had difficulty in doing so. The information was copied into an enumeration book by the district registrar. These were sent, together with the original schedules, via the superintendent district registrar, to the General Register Office in London. It is microfilmed copies of these books which we now have access to.

The original books are kept at the National Archives at Kew and are not generally available to the public. The schedules were usually destroyed after clerks had checked them against the enumeration books, extracted statistical information and made certain notes and ‘corrections’.

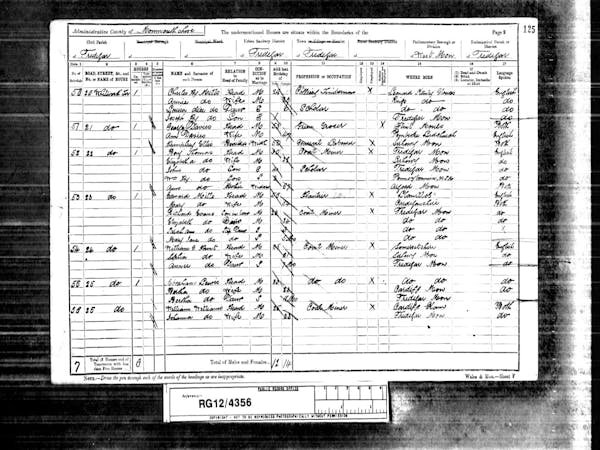

The returns for each decennial census have a reference number which reflects the Government Department responsible for it and the year in which it was taken. So the first two are labelled HO for the Home Office and the remainder are prefixed with RG for the Registrar General’s Department.

Earlier census returns from 1801 to 1831 were largely the responsibility of Overseers of the Poor and the local clergy. 1841 was the first attempt to collect information about every individual in the country and a whole new organisation structure and process was established, becoming incorporated with the local and central government structure responsible for General Registration.

Clerical staff and local enumerators were appointed and the country was divided into more than 30,000 enumeration districts, based on the old hundreds structure, later the Poor Law Unions formed in 1834 and under the auspices of Superintendent Registrars.

The 1911 census, in contrast to the earlier returns, is comprised of the original householders’ schedules and census enumerators’ summaries.

Content

Each census from 1841 contains basically the same type of information which is a valuable building block in the creation of family trees. Details include the address for each scheduled household; the name and an indication of the sex of each occupant; his or her age and occupation.

Except in 1841 the relationship to the head of the household is given and so is the place and county of birth and marital status.

In English and Welsh censuses, birth places outside England and Wales are usually shown as the country only, e.g. Scotland, Ireland or Australia. In 1841, these would be abbreviated to S (Scotland), I (Ireland) & F (Foreign Parts).

Dates of the enumerations and additions to the information previously recorded are shown below:

Enumerations and additions

1841 HO107

Age - usually rounded down to nearest 5 years for persons over 15.

Place of birth defined as whether or not in the county of enumeration.

Address may be no more than a street or even a village name.

Only one forename is noted.

1851 HO107

Also specifies whether a person is blind, deaf or an idiot.

Tradesmen usually defined as master, journeyman or apprentice.

Numbers of employees of a master given.

1861 RG9

No additions or changes

1871 RG10

Also distinguishes whether a person is imbecile, idiot or lunatic.

1881 RG11

No additions or changes

1891 RG12

Also records the number of rooms occupied by a family if less than 5.

Records whether a working person is an employer or employee or neither.

1901 RG13

Records if working at home as well as details above.

Now 4 categories of disability: deaf & dumb; blind; lunatic; imbecile or feeble minded.

1921 RG15

This census was published in 1922. It provides greater detail than any previous census as, in addition to the questions asked in 1911, the 1921 returns also asked householders to reveal their place of employment, the industry they worked in and the materials they worked with as well as their employer’s name.

1911 RG14

This is the first census that retains the household schedules rather than copying them into enumerators’ books, so you could be looking at your ancestor’s handwriting. Unlike earlier censuses, these returns include soldiers serving overseas. The numbers of years a couple has been married is recorded along with how many children (both dead and alive) they have had.

The basic reference number for the census year is followed by a 3 or 4 digit number, known as the piece number, which identifies the part of the country covered by the returns. These were originally related to the Poor Law Union districts which were the same as the districts used for General Registration.

There are indexes and finding aids to help identify the right number for the area you are interested in. Each piece is divided into enumeration districts and each alternate page is printed with a consecutive folio number, stamped on the top right hand corner. The page numbering re-starts with the next ED but the foliation continues to the end of that piece.

At the front of each enumeration district is a page describing the area included and there are spaces on each form for details of the district, village, parish (civil and ecclesiastical) etc. to be included. The ecclesiastical parish name may be a guide when looking for baptisms in the family.

Although occupations were given for most adult males there were ‘hidden occupations’ not recorded, particularly where women working at home were concerned e.g. on farms or as weavers etc. Wives may be described as, for example, farmer’s wife or butcher’s wife. Children may be similarly defined in terms of their father’s trade or occupation.

Common abbreviations & conventions include:

Ag Lab - Agricultural Labourer; FS - Female Servant; MS - Male Servant; Mar - Married; W - Widow or Widower; Unm or S - Unmarried or Single. ‘in-law’ may be ‘step’ relative.

As well as the basic information about family relationships, which may cover more than two generations in the same household, the census also provides vital knowledge about place and approximate year of birth. This helps to identify the right birth details for obtaining certificates and baptismal records which may be researched further.

Knowledge of a wife’s forename can help to pinpoint a correct marriage partner e.g. on UKBMD or FreeBMD. Occupations may also help to provide back up evidence of identity. The benefits of using census information in building up a family structure are greatly increased if the family can be tracked over the full 70 years for which records are available.

Apparently unrelated household members noted as visitors or lodgers, and sometimes servants, may in fact be members of the extended family. Their surnames may give clues to in-laws or marriage partners. This is also the case when in-laws are specifically recorded. Extended families may well inhabit houses in the same locality and it is often worthwhile doing a search of a whole neighbourhood.

In this way, migrant communities can be identified and may hold the answer to questions about why people moved from their birthplace. It was not uncommon for married children to live in the same street as their parents and young children are often found in the care of their grandparents or aunts and uncles - who may or may not have the same surname.

Additionally, illegitimate children often lived with relatives instead of with their mother if she maried someone who was not the child’s father.

Where to find the census

The enumeration books have been filmed and are available to the public on microfilm or microfiche as well as online. The 1911 returns have been scanned as digital images.

The returns for the whole of England and Wales for all years of 1841 - 1911 can be seen at the National Archives (TNA) in Kew. Access is free at TNA. In addition, copies of these fiche or films are becoming more widely accessible across the country.

Copies of returns for local areas are usually now found at county record offices and local studies sections of reference libraries. LDS Centres can usually obtain microfilm for a specific area on request for a small fee. The Society of Genealogists has a large collection of census films available for use in its library.

Most people will now look at the census returns and indexes via computers and the internet. Several companies have produced CDs of census films for individual counties for each of the census years.

Quality varies and some of the earlier census returns do not copy well and can be difficult, if not impossible, to read. But quality standards are gradually improving. Generally such CDs are scanned images of the enumerators’ books and are not fully indexed.

They are not searchable databases but there is the advantage of being able to use CDs at home and they offer the facility to save and print images of relevant pages.

The images can also be manipulated and magnified to help interpretation of difficult writing. For 1881 the LDS has produced a set of CDs of full transcriptions, indexed and searchable, for the whole country, which is freely available at their web site: familysearch.org.

Recently great advances have been made in providing on-line Internet access to the censuses, with the key feature being a computerised, searchable index of people enumerated.

There are now a number of commercial organisations (including Ancestry; FindMyPast; The Genealogist; British Origins; Genes Reunited) which operate pay per view or subscription websites giving access to original images of census documents, via the internet, together with transcripts and indexes.

This is in addition to the National Archives site for the 1901 census, which has a free searchable index but pay per view images or transcriptions as has the recently published 1911 census.

Coverage is increasing rapidly although there can be problems with mis-transcriptions, missing pages and limited access to some parts of the original documents (e.g. enumerators’ walks), depending on the web site used.

Various strategies can be developed to overcome some of these problems, including the use of wild card symbols and searching on key words and dates.

Scottish censuses remain in Scotland and all are indexed with images online through the ScotlandsPeople website at scotlandspeople.gov.uk.

The surname indexes for all years from 1841 to 1901 can be searched on ancestry.co.uk. An index and transcription to the 1881 census of Scotland is included on the CDs produced by the LDS.

Sadly Irish censuses before 1901 have not survived and little is online. Images and online indexes for the whole of Ireland in 1911 and 1901 are now available at census.nationalarchives.ie.

Finding aids and name indexes

There are now many different finding aids to help identify the area to search for your ancestors in each of the census years. The first task is to find the most likely place your ancestor will be living in the relevant census year.

Likely addresses may be found on certificates, in trade directories or in returns from other census years. Even with a computerised, searchable index, there is a frequent need to differentiate between people with the same name and location.

Many family history societies have produced indexes for the registration or enumeration districts within their areas. These vary greatly in content - some are almost full transcriptions and others simply provide a piece number and folio number for each occurrence of a particular surname.

Many of these booklets are available as reference copies at TNA or at SoG. They can also be obtained for a small price from the societies concerned.

FreeCEN is a website set up to provide free searchable access to census information. The internet pay per view sites may offer a free index which links to the (paid for) image of the page and/or a transcription.

However, it is not always possible to find someone in an index, as mentioned above, for reasons of mis-transcription, missing pages, mistakes made by the original enumerator or because there are too many candidates to check them all out or determine, with any certainty, which one is correct.

The internet site genuki.org.uk provides many useful links to census indexes, transcriptions and finding aids. Registration districts and sub districts and piece numbers can also be identified from links on this site as well as the LDS film numbers for the appropriate microfilm. See also the LDS catalogue on familysearch.org.

Common problems

There are many reasons why census information may not be 100% accurate. Details found on one census return should always be viewed in conjunction with those from other years, as well as with knowledge gained from other sources, to ensure the best possible standards of evidence.

Reasons for inaccuracy include: lack of knowledge of the informant - especially when accounting for visitors and lodgers; lack of proper understanding of the process e.g. people away from home enumerated in two different places (or neither!); people who lied for reasons of vanity, (im)morality, social standing e.g. tradesmen declaring themselves to be gentlemen, or shame e.g. about illegitimacy; interpretations provided by the enumerator or clerks, or personal bias or assumptions made by the enumerator.

Spellings of names of people and places will often be those of the enumerator and as he (or she) heard them.

Although households were usually listed in descending order from the head of the household to the youngest child, in the 1841 census, in particular, relationships cannot be assumed for those with a common surname.

An elderly man and woman with the same surname may be brother and sister rather than man and wife. Younger people in the household may be nephews and nieces or even grandchildren.

People missing from the census, and not just missing from an index, may have been away from home for a variety of reasons, legitimate or otherwise.

They may have been abroad in the services, at sea or travelling overnight. They may have been leading a double life. It is always worthwhile checking workhouses, hospitals and other local institutions, prisons, barracks and ships in port.

Often people in institutions like asylums were recorded by initials to give inmates a degree of privacy.

There is a general problem in that women‘s occupations may often go unrecorded reflecting, amongst other things, the importance Victorian society placed on the role of women in the home and the status attached to men as breadwinners and sole providers.

Online search tips

- less is more – you may not need to complete all the boxes - generally the fewer boxes completed, the better

- be aware of transcription errors

- can you use character replacements (wildcards)?

- first letters are often misread

- abbreviated forenames may not come up

- search under forename, age, place etc rather than surname

- enumerators made errors too

- search all indexes available – results can differ between sites

- local expertise may recognise local names and places better

- do not always rely on indexes!

Bibliography

Census: the Expert Guide by Peter Christian and David Annal, TNA, 2008.

Making Sense of the Census Revisited: Census Records for England and Wales,1801-1901.

A Handbook for Historical Researchers by E Higgs, University of London, Institute of Historical Research, 2005.

How to get the best from the 1911 census by John Hanson, Society of Genealogists, 2009.

Local Census Listings 1522-1930: Holdings in the British Isles by Jeremy Gibson and Mervin Medlycott, Federation of Family history Societies, 1994.

Conclusion

The Victorian and later census returns provide not only the basic information essential in the construction of family trees, together with a way of bridging the gap between General Registration certificates and earlier parish records, but they are also valuable tools to help us understand the lives of our ancestors within the context of the society in which they lived.

This document was written by Geoff Swinfield and edited by Else Churchill

© Society of Genealogists 2017,2021

Join us

As a member, you can make the most of our resources, access our experts, and find a welcoming community of people interested in family history and genealogy.

We all have roots. Let’s find them together.